Modernism from the Heartland: Gordon & Jane Martz

When two newlyweds in the Hoosier State tackled modern ceramic design, the whole world took notice.

The story of Gordon and Jane Martz's contributions to modern design and ceramics begins very simply: Boy meets girl. Girl marries boy. Boy and girl move to girl's home town. The Museum of Modern Art calls boy and girl. Boy and girl's lives change forever.

The creators of Martz lamps and pottery met at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, where they were both students. Gordon and Jane Martz married when they graduated in 1951, and they began their married life by moving to Jane's home, Veedersburg, Indiana. Jane Marshall Martz was from the family that owned Marshall Studios, a lamp company founded in 1922 by Jane's grandmother, known affectionately in the family as "Muz". Jessie "Muz" Marshall had started her career hand-painting lampshades in her Indianapolis home. The shades led to lamp bases, and the bases led to a small Indianapolis factory producing a line of turned wood lamps with hand-painted shades. By 1951, the company had been in Veedersburg for ten years, in a building originally built as a WPA project. Marshall Studios was then in the hands of Jane's parents, Nicholas and Grace Marshall, who wanted the young couple to contribute their talents to the enterprise.

Pick and Choose: This color and decoration guide from a Marshall Studios catalogue shows how many colors and decors could be combined. Readers with a taste for advanced mathematics are invited to figure out how many variations were possible. [click this image to see a larger view]

Their talents were undeniable; both had had intensive ceramics and design training at the college, and Gordon's interest in engineering principles had been nurtured there, as well. Jane had gone to school for the sole purpose of getting the design and ceramics training she would need to expand and carry on the family business. Meeting Gordon there was lucky; Jane had not only found a husband, but someone she could work with as a team to realize all her dreams, and more. At Alfred, both Gordon and Jane had become first-rate ceramists, so their contributions to Marshall Studios would center around what they knew and loved best.

Veedersburg was a very small Indiana town of perhaps 1500 people, near the Wabash River, about 75 miles northwest of Indianapolis. Fortuitously for the Martzes' plans, it was in an area of clay soils, and had a history of ceramic businesses, although not ones based in fine design. Brick was what they made in Veedersburg; product from several local companies had been combined to build the famed "Brickyard" speedway used for the Indy 500 beginning in 1909. Gordon and Jane Martz began realizing their dreams by setting up a ceramics plant at Marshall Studios to produce lamp bases in the modern style they'd become trained in at Alfred.

Gordon began with some experimentation; the clay around Veedersburg was great for bricks, but yielded uneven results for pottery and ceramics. He eventually settled on a mixture of local and commercial clay, based on a formula he'd evolved at college. Once Gordon had invented the stoneware body he wanted to use, he and Jane began to design.

Coming into the Marshall family and company had shown Gordon that the company's customers appreciated the appearance of hand-made items, and that a hand-made look could be achieved under factory conditions. Although it was trickier to give factory-made ceramics that appearance than it was with painted lamp shades, Gordon and Jane Martz began devising ways to make it possible, and profitable.

The Martz Touch: Martz lamp bases were slip-cast for mass production, but in this shot, Marshall Studios employees can be seen applying incised decoration, designed by the Martzes, by hand.

Their basic tactic was to create different simple shapes in slip-cast ceramic that could be decorated in various ways, with techniques more commonly used by potters than in commercial production. A Martz design was never decorated with the decals and transfers common to most ceramic companies, and representational designs were seldom used. Gordon and Jane Martz broke their decorating techniques down to three simple methods that could be used singly, or in combination. There was incising, or scratching a design into a freshly glazed piece before firing. There was also dipping, which involved immersing a piece in a base color first, then dipping into other glazes to varying depths for a layered effect. And there was brushing, which involved lightly or loosely brushing glaze on to a piece, usually while it was being rotated on a vertical lathe. All three techniques could be learned by almost anyone, but making them look professionally applied was a skill the Martzes had to work hard to impart to others.

Fortunately, Marshall Studios had a work force - mostly family members at first - with a strong Indiana work ethic, and the three basic techniques began to be used on lamp bases the Martzes had designed. The first was the Martz No. 41, a simple columnar shape derived from the Bauhaus principles Gordon and Jane had been exposed to at Alfred. It also established the classic Martz design elements of an American walnut neck coming from the top of the ceramic base, and a walnut finial for the shade. Besides looking good, the walnut pieces utilized the Marshall Studios wood shop that had been set up to make wooden lamps. Beginning with this first design, the Martz tradition of making the product available in a wide variety of colors and decorations was established. Over two dozen glaze colors were eventually available, in both matte and gloss finishes. The No. 41 could be decorated with brushing, like black lightly brushed over dark blue, or incising, where the glaze color had a design scratched into it, so that the tan body showed through the glaze. The final flourish was the "Martz" signature incised on the base, next to the hole for the cord. With its simple, European good looks, so unlike the flashy, kitschy "modern" designs available from other companies, the No. 41 found a following, but there was more to come.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: This shot of the first Martz lamp design, the No. 41 shown on the left, shows the design quality of Martz lamps. In contrast, note the two badly designed painted plaster pseudo-Danish Modern lamps from another manufacturer at right.

The watershed product for Marshall was the Martz No. 101, an exquisitely simple teardrop shape in matte black. The Scandinavian-looking lamp was so pure in design, it came to the attention of a man who would change the fortunes of Marshall Studios for years to come. The man was Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., and he was with the Museum of Modern Art. Son of Edgar Kaufmann, Sr., who had commissioned "Fallingwater" from Frank Lloyd Wright, the younger Kaufmann was planning the 1953 Good Design Exhibition at MoMA. After seeing the No. 101, he made a telephone call to Veedersburg.

Gordon Martz hit it off with Edgar Kaufmann - or was it the other way around? - and the Martzes were invited to show the No. 101 in the exhibition. The two men found that they agreed on so many principles of ceramic design that Kaufmann asked Gordon Martz a favor. He needed an example of really dreadful bad taste for the show, to illustrate to museum-goers the difference between good and poor design. Using any manufacturer's real product for the purpose was out of the question, because of the possibility of a lawsuit. Gordon Martz obliged Kaufmann and MoMA with a howler of a bad lamp design, finished in a lurid metallic glaze. Shown uncredited, the lamp not only made its point, it enhanced the appeal of the No. 101. Stores began ordering the No.101 for customers who had seen it at Good Design, and the Martz line began to sell. And sell. And sell.

The Design MoMA Loved: The No. 101 was selected by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. for the 1953 Good Design exhibit. The timeless design was produced until Marshall Studios was sold in 1989. The late shade design shown is not the same as the example in MoMA's permanent collection; the original shade was smaller.

The No. 101's success began three and a half decades of amazing commercial and artistic growth for both the Martzes and Marshall Studios. By 1956, the complexity of the business had grown to the point that Jane's brother John Marshall came in to handle the business end that Gordon and Jane didn't have enough time for. John's wife, Carolyn Marshall, also helped when her time allowed. The Martzes were now free to work on new designs and new decorations in the signature Scandinavian-based Martz style, which followed in fast profusion. Big lamps, little ones, tall narrow ones, and short squat ones began pouring out of the little plant on Mill Street, which eventually wasn't so little any more. Marshall Studios evolved into a very complex operation, making everything in-house, even lampshades. In an age before computers were available to keep track of orders, scheduling, and inventory, Marshall offered dozens of lamp styles in dozens of colors and more dozens of decorations, not to mention shade options. There were literally thousands of possible combinations, and Marshall Studios became famous for turning out huge orders of them error-free. Jane Martz was in the thick of all this activity, helping Gordon design, and doing whatever was needed to iron out problems of any kind. After 1960, Jane turned her hand to sales, where she proved to be a powerhouse.

Full Tilt: Here's how you provide shades for a thousand lamps every month. Note that different shade designs are running on the line at the same time; the non-computerized Marshall factory was set up to produce thousands of design variations.

By the early 1960's, sales had climbed to a point of around 1,000 lamps a month. Marshall Studios products of all descriptions were carried by department stores coast-to-coast, and Martz lamps enjoyed strong contract sales to hotel chains like Sheraton, due to the high quality and durability of the product. Martz lamps even went overseas. The General Services Administration (GSA) was an excellent Martz customer, purchasing lamps for American government offices and embassies all over the world. The Marshall Studios factory became expert at wiring for European voltage. Gordon Martz tells a funny story on himself about one batch of lamps he knew was destined for the American Embassy in Moscow: Before the felt was glued to the bottom of one lamp, he wrote "Kruschchev is a bum!" on the base. The "secret message" was duly shipped to Russia, where it may still exist, undiscovered. Although it was a fairly gentle rebuke at the Soviet leader, the joke could have been troublesome if it had come to light. At least the GSA would have known Gordon was a true-blue American.

Let's Dish: Wisteria (top) and Dot Dash (bottom) were two of the many lines of dinnerware produced by Marshall Studios. The Martzes' affinity for Scandinavian design can be seen in the Wisteria photo; that's Dansk's famed Fjord flatware beside it. Note the dual-purpose goblet/candlestick design.

By the 1970's, Marshall Studios products included the highly popular line of lamps, plus dinnerware, serving pieces, canisters, planters, carafes, cruets, tile-topped tables, bookends with inset tiles, and ashtrays. There was even a line of Martz-designed altarware offered through Cokesbury, a company specializing in church furniture, vestments, and supplies. Marshall employee Leon Lowe, who was a Veedersburg local prized within the company, usually decorated the altarware. Lowe's innate talent for reproducing decoration surpassed that of many trained ceramic artists, and Gordon Martz eventually gave him the accolade of allowing him to "freehand" decoration without using a cartoon.

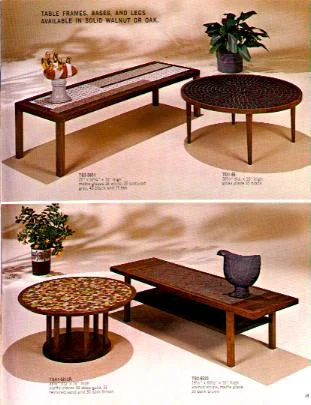

Make the Most of It: The same wood shop and ceramic equipment used for Martz lamps were used to produce these tile-topped Marshall Studios tables. The black hen on the table at lower right is an example of Gordon Martz's studio work. The sculpture on the other table is by Marshall Studios employee John Gunther.

Nothing went to waste at Marshall Studios; every person, talent, opportunity, and resource was used to the fullest. Cuttings and trimmings from the wood shop were used to make small items like bookends. Gordon and Jane Martz's design and photography skills produced the company catalogues. The family's affiliation with the Methodist Church helped it to realize there was a need for altarware. Even the company watchdog and mascot, a bulldog named Brutus, lent his considerable personality to appearances in Marshall's sales literature.

Justifiable Pride: On Martz lamps, the entire lamp was UL-tested and approved, not just the socket. The attention to safety was the key to Marshall's strong hotel and government contract sales. That's the Martz signature beside the cord hole.

Unfortunately, nothing lasts forever, not even the excellence achieved by the Martzes' talent and the strong work ethic of the Marshall family. By the late 1970's, the demand for Modernism was slackening, and the traditional "family business" model of the Marshall Studios operation was becoming uncompetitive, through no fault of the company. Ceramics were being made more cheaply in Asia, and customers had changed as well; price had become more important than style or quality. By 1989, the sad decision was made to sell the business, which was closed by the new owners shortly thereafter. Gordon and Jane Martz retired, and so did John Marshall and his wife Carolyn.

Today, the Martzes are still very active people, at a time of life when most folks are content to sit and re-live their memories. Gordon and Jane live in Arkansas, in a community where many other artists reside; Gordon has been able to return to the studio pottery that was his first professional interest. His activities include showing his current studio work in galleries and juried shows, and his leisure-time loves, gardening and golf. Jane Martz is working on an autobiography telling about her life and the three generations of artistry in her family. John Marshall died in 1990. His wife Carolyn has remained in Veedersburg; she is highly active in the Methodist Church. In 2000, she was elected to a four-year term as Secretary of the United Methodist General Conference.

As befits their roots in the heartland, Gordon and Jane Martz are kind and generous with their friends and admirers. After all their years running a busy enterprise like Marshall Studios, they're able to handle anything. Even something like a magazine writer calling out of the blue, asking nosey questions, wanting to know all about a pair of young newlyweds who devoted their lives to putting Veedersburg, Indiana on the map of Modernism.

Buying Martz, Old and New

Old Martz:

Martz lamps have become very popular with collectors; single lamps regularly auction at Treadway and LAMA for $200-300. If you are looking for Martz lamps, here are some tips:

- The most popular Martz lamps are the ones with incised decoration; expect to pay a premium for these.

- A matched pair of lamps is worth more than two mismatched singles; count on a premium of at least 25%.

- Marshall Studios made some Gordon Martz-designed floor lamps in walnut, with and without tile-topped tables. These are very rare in good condition.

- Original shades increase value, and an original Martz walnut finial is necessary for a lamp to be considered complete.

- Some Martz lamp designs are a ceramic shape sitting on a walnut base, with a walnut cap on top of the ceramic. The walnut neck comes out of the top cap. These designs do not have the Martz signature; a Martz catalog picture or expert opinion should be relied upon to verify that such a lamp is actually a Martz.

- Missing Martz shades are difficult to replace, since the natural materials and drum shape used are not widely available today in retail stores. Shades can be replaced or refurbished by a company specializing in custom shades.

- Due to the popularity of Martz lamps, other companies made similar-appearing lamps, usually in plaster with a painted finish. A Martz lamp is always ceramic, or wood, or wood inset with tile, never plaster.

- There is a wide variation in the values of other Martz and Marshall Studios items; condition is important, and incised designs are usually the most sought-after. Complete sets of dinnerware are very rare, and buyers should expect to pay accordingly.

- Works marked "Martz Studios" are not Marshall Studios items by Gordon and Jane Martz. The "Martz Studios" mark appears on works by potter Karl Martz, who was not related. Karl Martz's son, Eric Martz, has a website (click here) with excellent information on Martz Studios and Karl Martz.

New Martz: Since his retirement from Marshall Studios, Gordon Martz is once again creating studio pieces.

Production and Studio pieces of Martz pottery are offered for sale here at www.jetsetmodern.com

Call or write for more information.

The author and Joe Kunkel wish to express gratitude to Gordon and Jane Martz for sharing their memories of Marshall Studios, Martz pottery and lamps, and their careers and family history. We are also grateful to the Martzes for their invaluable review of this article, and for their suggestions.

All images of Marshall Studios and Martz designs in this article are from the final Marshall Studios Commercial Catalogue Number 35, circa 1988. © 2002 Gordon and Jane Martz. Used by permission of Gordon and Jane Martz.

The Martz Script Signature ® appears by permission of Gordon and Jane Martz.

SOURCES

Marshall Studios Commercial Catalogue No. 35, 1988. Privately printed.

Telephone interview by the author with Gordon and Jane Martz, March 12th, 2002.

Correspondence from Jane Martz to the author, various dates between March 12th, 2002, and March 14th, 2002.

Response Daily, Issue 1, Page 4, May 14th, 1998. Response Magazine for United Methodist Women Website, http://gbgm-umc.org/response/

United Methodist News Service press release, dated May 8th, 2000.

A Treasury of Scandinavian Modernism, by Erik Zahle. New York, Golden Press, 1961.

Decorative Art in Modern Interiors, 1968/69 edition. Edited by Ella Moody. New York, Viking, 1968.

Bennett Brothers 1962 "Blue Book" Catalogue, Bennett Brothers, Chicago. Privately printed.

The Legendary Bricks of Indy, by John E. Blazier. The Gavin Historical Brick Company Website, www.historicalbricks.com.

To search this entire site by keyword, click here.

© copyright 2015 © copyright 2002 Joe Kunkel and Sandy McLendon and Jetset - Designs for Modern Living. This article was published on March 15, 2002. Republished March 18, 2015. All Rights Reserved.